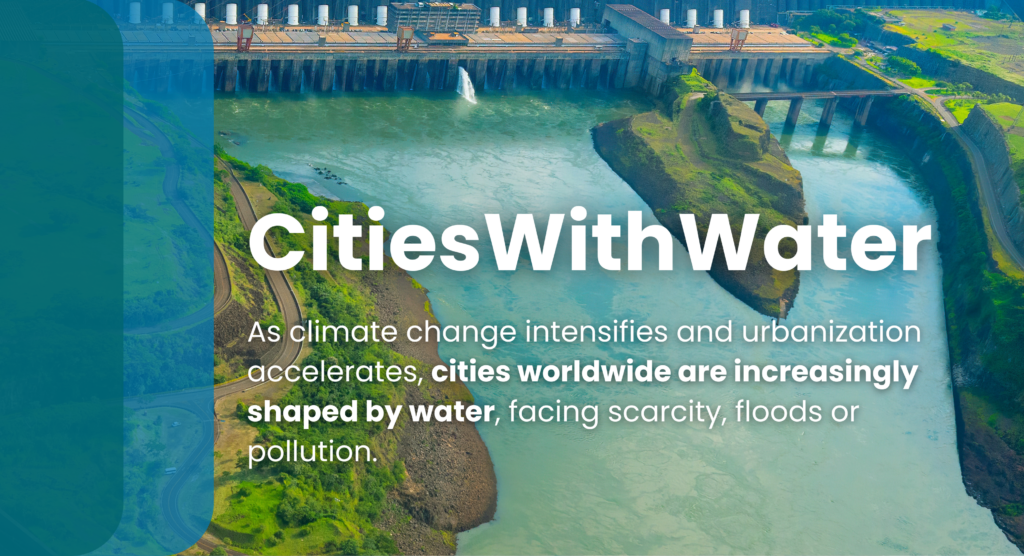

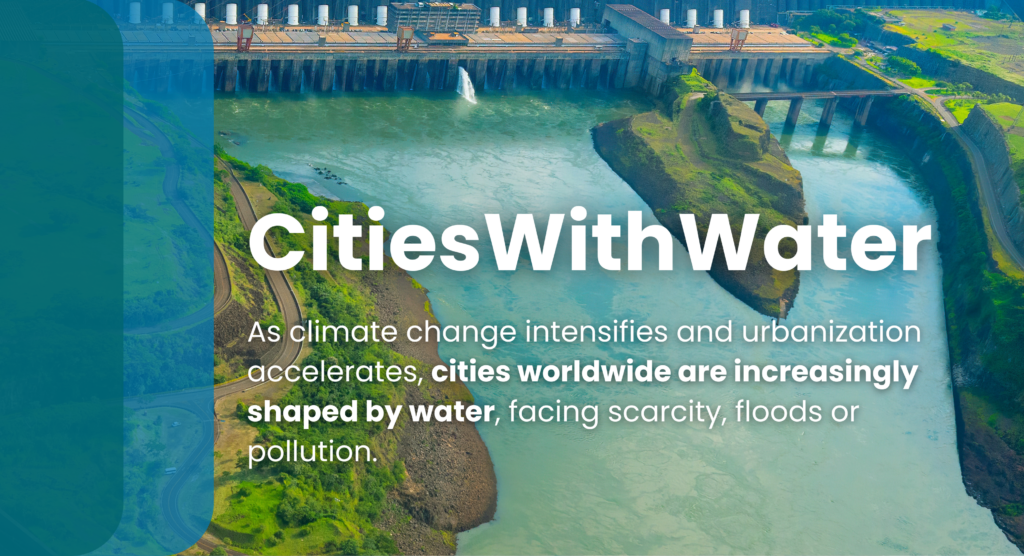

As climate change intensifies and urbanisation accelerates, cities around the world are increasingly defined by water. In some cases they have too little, sometimes too much, or sometimes water that’s too dirty.

The CitiesWithWater initiative has placed water firmly on the urban sustainability agenda. Through a webinar series and an international photography competition, CitiesWithWater is raising the voice of cities and learning how they can and should act now to safeguard water systems, human well-being and ecosystems.

In the recent webinar titled “Too Much“, hosted in collaboration with the World Water Council, city leaders and technical experts explored how urban areas are preparing for or recovering from floods, storms, sea-level rise and the cascading impacts of climate change. This second installment in the CitiesWithWater series followed the success of the first (“Too Little”) and sets the stage for the upcoming webinar, “Too Dirty”, which will delve into water pollution and the urgent need to protect downstream ecosystems and coastal waters.

The “Too Much” webinar (18 June 2025) highlighted that flood-related disasters have increased by 134% since 2000 (WMO, 2021), a statistic that no city can afford to ignore. Panellists from cities including Kumamoto (Japan), Lusaka (Zambia), Ningbo (China), and Larissa (Greece) shared powerful case studies on how their municipalities are adapting to flood risks.

What happens upstream doesn’t stay upstream. With the UN Ocean Conference (UNOC) recently reaffirming the vital links between terrestrial and marine systems, CitiesWithWater is also working to bridge the gap between urban water governance and coastal health. Dirty or excessive water from cities — be it stormwater, untreated sewage, or plastic waste — flows downstream, posing major threats to fragile estuaries, coral reefs and fisheries.

In the upcoming “Too Dirty” webinar, these linkages will be explored more deeply. How can cities protect downstream ecosystems from pollution while safeguarding human health and livelihoods? What does it take to reduce nutrient runoff, manage industrial discharge and treat wastewater effectively in dense urban settings?

With the Convention on Wetlands COP15 fast approaching in July 2025 in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, CitiesWithWater is also drawing attention to the vital role of urban wetlands. These ecosystems, often overlooked in city planning, act as natural sponges that absorb floodwaters, filter pollutants and recharge aquifers.

Wetlands also serve as critical habitat for biodiversity, cooling spaces for urban residents and buffers against sea-level rise and coastal storms. Yet urban expansion continues to degrade or destroy them. Between 1970 and 2015, 35% of the world’s wetlands were lost (Ramsar Global Wetland Outlook, 2018), and many that remain are under pressure from pollution, encroachment and climate change.

Cities that invest in wetland protection and restoration — like Cape Town’s rehabilitation of the Zandvlei Estuary or Kolkata’s use of its East Kolkata Wetlands for natural sewage treatment — are leading the way in reintegrating nature into urban water systems.

Urban water systems are not just pipes and pumps. They are the veins and arteries of a living city to sustain health, enable growth and connect communities. Yet they are under serious threat: