Malmö: Where indigenous birds mingle with global travellers

About the author:

Erik Hirschfeld is a well-known Swedish birder fortunate to live in Malmö. He is the author of several books, including The World’s Rarest Birds (2013) covering global bird conservation and Fåglarnas Malmö (2011), covering Malmö’s birds and their interaction with humans. He has served on bird record committees in Sweden, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates, and has been involved in several scientific expeditions, especially in the Middle East. Fifteen years ago he founded Vilda Malmö, initially a lose network of nature guides, in order to highlight Malmö’s natural environment to its residents. Today he spends his birding time between being an active bird bander, studying migration of seabirds, and running Scandinavia’s largest bird tour company, AviFauna. He frequently gives illustrated talks on birds to both beginners and professionals, and guides people interested in birds for Vilda Malmö.

A crossroads for migration

Perched at the southern tip of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Malmö offers migratory birds a convenient shortcut across the water to Denmark and mainland Europe. Much like the famed Falsterbo, just 30 km down the coast, Malmö is perfectly positioned along a major migratory route. When on the move, many landbirds avoid vast bodies of water and instead funnel through areas with shorter crossings. Add the iconic Öresund Bridge into the mix, and you’ve got a ready-made flight path. On windy days, birds of prey can often be seen using the bridge as a navigational aid during their spring and autumn journeys.

But geography alone doesn’t explain Malmö’s birding success. Migrants won’t stop unless there’s a good reason to. That’s where Malmö’s clever city planning and habitat diversity come into play. The city is a patchwork of microhabitats catering to a dazzling variety of birds with different needs.

Red-necked Grebes

Black Redstarts (male & female)

Habitat hotspots and urban adaptations

Take the coastline, for instance. Stretching out in a mix of sandy, muddy, and rocky areas, it serves up a smorgasbord of habitats for wading birds, perfect for sanderlings, bar-tailed godwits, and purple sandpipers. In the harbour, boulders placed as wave-breakers become life-saving shelters for tired migrant passerines hiding from hungry sparrowhawks. Seabirds following the east-west coast are often seen rerouting dramatically to avoid land, providing unforgettable spectacles for those positioned at just the right windy vantage point. In fact, gannets now winter offshore in large numbers, mingling with massive flocks of cormorants. Two species of albatross have even made surprise appearances here, an astonishing rarity in these parts, and sooty shearwaters from New Zealand have become almost annual guests.

One of Malmö’s most productive hotspots is the stretch along Ribersborg Beach. Here, seaweed is cleared to please beachgoers and then dumped near a hedge by Lagunen harbour. That unassuming pile teems with insect life and sits beside a dense alley of trees, offering both food and shelter to weary warblers. Come migration season, that compost pile becomes a lifeline. It’s also the site of an ongoing bird banding project, and when the seaweed dries out, it’s used to fertilise Malmö’s public lawns, an example of ecology in action.

Inland, a series of freshwater ponds offers safe nesting and feeding areas to mute swans, little grebes, and the red-necked grebe, a striking species whose springtime courtship dances can be enjoyed up close, even without binoculars. These ponds give Malmö residents front-row seats to one of nature’s most theatrical performances.

Oystercatcher

Barnacle Geese

Red-necked Grebe

Common Gull

Barnacle Geese

Barnacle Geese with two rare Red-breasted Geese

Birds in the parks and cemeteries

Every spring, a headline act unfolds in the city. Ravens nest in an old shipbuilding crane beside a waterfront residential zone, an urban first in Sweden. Unlike the domesticated Tower of London ravens, these are wild birds, voluntarily choosing Malmö’s industrial relics as breeding grounds.

The city’s beloved parks are no less impressive. Hammars Park, with its wild undergrowth, attracts songbirds like blackcaps, wood warblers, and goldfinches. Pildammsparken, with its elegant promenade and wide pond, plays host to ducks, gulls, and breeding great crested grebes showing off their curious greeting displays in spring. It’s a favourite among preschoolers, grandparents, and birders alike, offering easy access and rich wildlife. Slottsparken, meanwhile, offers a blend of trees and water that appeals to both breeders and migrants.

In late morning, gulls descend from the coast to bathe in the parks’ freshwaters. Tufted ducks and common gulls, with nesting grounds as far away as Siberia, make Malmö their winter base. Come late February, they’re joined by the first migrant lesser black-backed gulls, newly arrived from central and eastern Africa. Meanwhile, black-headed gulls spend the colder months here after journeys from Finland and the Baltics. Banded individuals, some as old as 30, have revealed fascinating life histories stretching across multiple cities and countries. The combination of being raised and spending the winter in highly urbanized habitats seems to be favorable to longevity.

St Pauli Cemetery, oriented north to south, is another seasonal hotspot, especially in spring. Here, you might glimpse the cryptic wryneck or the elusive ring ouzel, more commonly found in the remote fjells of summer. Redstarts regularly nest here too, making the cemeteries a true urban oasis.

Rooftop nesters and winter guests

Even Malmö’s high-rises play a part. Districts like Västra Hamnen, Dockan, and Limhamns Sjöstad resemble mountainous terrain to birds like the black redstart, which now echo their melodic calls through Malmö’s urban canyons. Some individuals even winter here, finding refuge in the evergreen ivy on buildings near the central station, alongside European robins.

The charismatic oystercatcher also makes its urban presence felt. Arriving in late February, they roost in flocks on jetties used by swimmers in summer before fanning out to nest on flat rooftops. Common gulls, meanwhile, often share these rooftops, while house martins and common swifts each have their architectural preferences. Clay nests on high buildings suit the martins, while the swifts prefer roof tiles on villas in Malmö’s western suburbs.

And let’s not forget the barnacle geese. Once Arctic-bound migrants, they now breed in Malmö in huge numbers, a mix of introduced birds and natural colonists. In May, local geese look skyward as their distant cousins pass overhead in dramatic, noisy formations, en route between the Low Countries and their Novaya Zemlya breeding grounds. Some Malmö-born geese have even been spotted in the Arctic, and vice versa.

Oystercatchers

Of course, the benefits of this biodiversity aren’t just for the birds. Access to urban nature is known to boost human well-being, and Malmö makes it easy to connect with the wild. Through the Vilda Malmö (Wild Malmö) program, residents can join free expert-led tours covering birds, bats, trees, marine life, and more, kept to small, intimate groups. For those who prefer to look for urban wildlife on their own, there are information signs placed around the city, with photos or drawings of the local fauna.

Malmö’s love of birds runs deep. Even its bird alert app, usually the domain of avid birders, has over 1,000 subscribers, proving that in this city, the skies above are just as captivating as the streets below.

World Wetlands Day is celebrated annually on 2 February, in commemoration of the initial signing of the Convention on Wetlands in 1971, in the Iranian city of Ramsar. This year, the theme is “It’s time for wetlands restoration” linking two important biodiversity components - wetlands protection and ecosystem restoration.

Wetlands and restoration

Despite being the world’s most productive ecosystems and crucial to human well-being, wetlands continue to experience extremely high rates of decline and degradation: an estimated 35% of wetlands have been lost since the 1970s. To prevent further losses and secure the necessary ecosystem services that wetlands provide – such as water purification, climate change mitigation, food and building materials, and flood control – the restoration of these important inland water and coastal systems are urgently required.

Ecosystem restoration has increasingly become a priority for scientists, politicians, officials and environmental activists in recent years as a critical approach to curb biodiversity loss and promote resilience to climate change. As such, the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, a 10-year push to halt and reverse the decline of the natural world, was launched in 2020. Through this year’s Wetlands Day theme, the UN Convention on Wetlands is calling for global restoration efforts to include the rehabilitation of wetlands.

Restoration acknowledged at high-level UN meetings

In 2022, urban wetlands were recognized as critical to human well-being at the UN Convention on Wetlands’ 14th Conference of Parties. During Ramsar COP14 in Geneva and Wuhan, Parties were called upon to take appropriate and urgent measures to achieve the goal of halting and reversing the loss of wetlands globally.

Also in 2022, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s 15th Conference of Parties in Montreal and Kunming witnessed the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which includes under its Target 2 an aim that, by 2030, at least 30% of areas of degraded terrestrial, inland water, and coastal and marine ecosystems are under effective restoration.

It’s time for restoration of urban wetlands

The loss of wetlands noted above is particularly prevalent in cities. Urban wetlands are vulnerable to the adverse impacts of urbanization as they tend to be undervalued and therefore often converted or used as dumping grounds. However, while the challenges of urbanization to wetland health are profound, so too are the opportunities for wetland restoration.

As part of the newly adopted Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework mentioned above, Parties adopted the decision titled Engagement with subnational governments, cities and other local authorities to enhance implementation of the post-2020 Global biodiversity framework and its accompanying revised Plan of Action on Subnational Governments, Cities and Other Local Authorities (2022-2030), which recognizes the vital role that cities and local authorities play in the implementation of the Global Biodiversity Framework – including by restoring urban wetlands and thereby contributing to Target 2. On the CitiesWithNature Action Platform, the CBD-recognized platform for cities to use for monitoring and reporting on their actions for biodiversity, the restoration and protection of urban wetlands can be recorded by Cities under Commitment 1 titled “Protect, Connect and Restore Ecosystems” and specified under two actions: “a) Restore and/or rehabilitate terrestrial, freshwater, and coastal ecosystems” and “(b) Increase protected areas.”

Globally, cities are increasingly acknowledging the importance of protecting and restoring wetland areas. To acknowledge cities’ significant contributions to take care of valuable urban wetlands, the UN Convention on Wetlands established the Wetland City Accreditation Scheme.

Wetland City Accreditation – Encouraging a positive relationship with urban wetlands

The Wetland City Accreditation (WCA) scheme was launched in 2015 – during the Ramsar Convention on the Conservation of Wetlands COP12 in Uruguay – with the aim of improving local authority or authorities’ work in conservation and wise use of wetlands. The accredited Wetland Cities are intended to act as models for the study, demonstration and promotion of the Convention on Wetlands’ objectives, approaches, principles and resolutions. Cities become candidates for accreditation by applying to the official call for applications posted here.

The WCA scheme aims to encourage cities in close proximity to and dependent on wetlands, especially Wetlands of International Importance, to highlight and strengthen a positive relationship with these valuable ecosystems, for example through increased public awareness of their importance and participation in municipal planning and decision-making.

During the Ramsar COP14 in 2022, the second triennium Wetland City Accreditation Awards Ceremony took place to celebrate the accreditation of 25 new cities (listed below). These cities have joined the already existing 18 accredited Wetland cities that have since been tasked to maintain their accreditation.

Wetland City Network and Roundtable of Wetland City Mayors – sharing best practices among decision makers

To further promote the conservation and wise use of urban and peri-urban wetlands, and to share city-level experiences among city leadership, the Roundtable of Wetland City Mayors first took place in 2019, where a Wetland City Network was established to continue the work of the accreditation scheme and enable cities to achieve more and learn from other Wetland Cities. The 2nd Roundtable of Wetland City Mayors will take place in June 2023, in Amiens, France.

The 2022 accredited cities are:

Sackville (Canada)

Sackville was built on/adjacent to saltwater marshes which had been dyked and drained in the 1600s to become freshwater “dykelands”. Since then the Town has undertaken many projects to restore, protect and utilize them, including creating legal restrictions which are supported by laws at all levels of government. The wetlands include the internationally recognized Sackville Waterfowl Park.

Hefei (China)

Hefei has 118,200 ha of wetland area, with a wetland protection rate of 76%. The city has invested in the protection of the Chao Lake area, protecting 10 wetlands covering a total of 100 square kilometers. This has significantly contributed to aquatic ecosystems, water security and quality, and wildlife habitat – up to 562 wetland plant species and 303 bird species. The City’s strategies include nine wetland education centers, wetland protection volunteers and science popularization to enhance residents’ relationship with the wetlands.

Jining (China)

Jining City is known as the “Canal Capital” for its abundant water resources, booming business activities and cultural exchanges. Jining wetlands cover an area of 158,800 ha, with the wetland protection rate reaching 77.38% as a result of the government’s commitment to wetland protection. Nansi Lake and the Grand Canal – designated as a Ramsar site in 2018 – attract millions of migratory birds every year.

Liangping (China)

Lianping’s rivers, streams, lakes, reservoirs and small wetlands are protected by the City’s strategy of “comprehensive water management, wetlands nourishing the city”, and its adopted model of “small and micro wetlands construction with ecological conservation, pollution control, organic industry, and natural education”, to benefit the lives of communities surrounding the urban wetlands.

Nanchang (China)

Nanchang has a wetland area of 153,000 ha, which provides a major habitat for hundreds of thousands of waterfowl globally, and an important wintering place for Siberian white cranes. The City has protected 68% of its wetlands and restored more than 8,000 ha, enhancing the ecological functions of wetlands, the urban living environment, and the socio-economic development of the city.

Panjin (China)

Panjin’s wetland covers 249,600 ha, accounting for 60.8% of the whole area. Its wetland protection rate is 54.6%, with 124,000 ha of wetlands restored since 2018 – benefiting the value of rice, river crab, tourism and other wetland industries. Panjin’s coastal wetlands are home to 477 species of wild animals – including 78 species of national key protected wild animals – and a stopover or destination for millions of migratory birds, including the Saunder’s Gull, Red-crowned Crane and Western Pacific Spotted Seal.

Wuhan (China)

In Wuhan the Yangtze River (the third largest river in the world) meets its largest tributary, the Han River. Endowed with 165 lakes and 166 rivers, Wuhan has abundant wetland resources and a wetland rate of 18.9%. Ecological restoration is secured through legislative protection, ecological compensation, conversion of fish ponds to wetlands, restoration of degraded wetlands, and public participation.

Yangcheng (China)

Yancheng has two Wetlands of International Importance and one coastal wetland World Natural Heritage Site. By 2021, the protection rate of natural wetlands in the city has reached 62%, and the “Yancheng Yellow Sea Wetland ecological restoration case” is renowned for its global nature protection in densely populated and economically developed areas.

Belval-en-Argonne (France)

The Belval-en-Argonne municipality joined forces with several nature protection associations (e.g. Birdlife France), to purchase the ponds of Belval-en-Argonne, which were designated a Regional Nature Reserve in July 2012. Major restoration work on the dykes and sluices has been carried out to better manage the water levels, and a large inventory of ponds and amphibians to create awareness of the site’s biodiversity has been created.

Seltz (France)

Seltz is a European town in the northern Bas-Rhin Department, with a population of 3,400 and home to the Seltz nature reserve: the Sauer Delta. This 486 ha site is remarkable for its botanical richness (including willow beds, mudflats and reedbeds), hydrology and landscapes, as well as ornithology.

Surabaya (Indonesia)

As a result of Surabaya City’s low elevation, many estuarine mangrove and wetland ecosystems have formed, amounting to 1.722,68 km2 of wetland ecosystem (76.51% of the total area 2.251,62 km2). These wetlands are important for bird species, particularly migratory seabirds and shorebirds in the East Asia-Australia Fly Away. Urban planning initiatives, in cooperation with community associations, are addressing challenges such as river and coastal pollution, seasonal water scarcity and urban flooding.

Tanjung Jabung Timur (Indonesia)

Tanjung Jabung is located on the east coast, with its west coast stretching across 12 km of the Sungai Berbak river mouth, and 15 km south of Tanjung Jabung. The city’s mangrove forest fringe ranges from 200-500 m wide and consists mainly of Avicennia marina and Rhizophora species with about 10 species of large waterbirds, including milky storks.

Bandar Khamir (Islamic Republic of Iran)

With the longest wetland coastline in Iran, Bandar Khamir has started a widespread popular movement – comprising events, festivals, educational workshops and numerous learning centers – in recent years for the wise use of the wetland. As a result of increased awareness and education of the value of the wetland and its ecosystem services, the participation and involvement of different groups to protect the wetland has increased.

Varzaneh (Islamic Republic of Iran)

Varzaneh city is located 20 km from Gavkhouni International Wetland which is supplied by the ZayandehRud river that passes through the city. Because of the hot climate of the city, the river and wetlands have benefited residents’ livelihoods, including agriculture, animal husbandry and ecotourism.

Al-Chibayish (Iraq)

Many projects implemented in Al-Chibayish city have contributed to the revival and sustainability of its wetlands. These wetlands support infrastructure and basic services for the local population and economy, in addition to its unique scenery and ecotourism services. The marshes also support a unique cultural heritage that is characterized by its residents and their traditional handicrafts, landscapes and biodiversity – such as buffalo and wild birds.

Izumi (Japan)

Izumi City is known as the largest wintering site of cranes in Japan, where more than 10,000 hooded and 2,000-3,000 white-naped cranes migrate every winter. The wintering habitat comprises mainly rice paddies which have been protected by Japanese policies against development. One of the city’s pillars of city planning includes “A city where human happiness and environmental conservation go together”.

Niigata (Japan)

Niigata recognizes the multifaceted benefits of wetlands near the city and involves their citizens in protection activities – particularly for fisheries – such as including school children for environmental education. The Niigata community has a relationship with the waterfowl, such as swans, that roost in the wetlands at night and feed in the rice paddies of the city area during the day.

Ifrane (Morocco)

Ifrane is located in the heart of the Atlas Cedar Biosphere Reserve, and considered to be the “ecological capital” of the Kingdom of Morocco. The City is working to conserve its urban wetland ecosystems – Lake Zerrouka, the Aïn Vittel springs and Oued Tizguite – through many national regulatory measures and instruments for the protection of wetlands. With its partners, Ifrane Province is a pioneer in the restoration of wetlands by piloting the “Lake Dayet Aoua restoration project”.

Gochang (Republic of Korea)

There are two Ramsar wetlands in Gochang, both protected under the National Wetlands Protection Act. Gochang has restored the paddy fields since 2017, and restored the brackish water zone between 2016 to 2020. The area is surrounded by ecotourism activities, such as the open market, and educational programs that are creating awareness among the communities of the importance of restoring wetlands.

Seocheon (Republic of Korea)

The Seocheon Getbol wetland reserve – a UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site – is a designated migratory route for migratory birds between East Asia and Oceania, and home to 19 endemic species and three endangered invertebrates, supporting 100 species of waterfowl. The Seocheon County Ordinance operates the Wetlands Protection Committee, a public-private joint organization, to systematically preserve and manage wetlands through monitoring, restoration and waste collection.

Seogwipo (Republic of Korea)

The Mulyeongari Oreum Wetland in Seogwipo City is home to 15 endangered species of living organisms. Ecological specialists and local residents in Seogwipo City perform extensive ecological monitoring on a regular basis to protect the Mulyeongari Oreum Wetland.

Kigali (Rwanda)

The Kigali Wetlands have been threatened by human activities such as agriculture, human settlements, commercial and industrial activities – decreasing their capacity for flood and pollution abatement. In response, the City is implementing strategic ecological rehabilitation solutions such as the Kigali wetland masterplan, which supports the efficient and sustainable management and use of wetlands. As a result, all business activities inside wetlands were evacuated; Nyandungu wetland (121.7ha) was transformed into a recreational eco-park; and a study to rehabilitate five wetlands that cover 480 ha has been conducted to contribute to its Vision 2050 of developing a Green City.

Cape Town (South Africa)

Cape Town is a coastal city with numerous wetlands and is a recognized global biodiversity hotspot. The City aims to mitigate wetland damage through innovative policies and plans, wetland offset projects, best-practice wetland management and restoration, people and conservation programmes, skills development, job creation, plus the Mayor’s priority water quality programme addressing impacts to and rehabilitation of the City’s larger wetlands.

Valencia (Spain)

L’Albufera de València is a wetland culturally linked to the community’s heritage, including traditional fishing and rice cultivation. Since the 1970s, Valencia’s City Council has played a fundamental role in the site protection and planning, which has resulted in the lagoon and coastal forest being declared a Natural Park in 1986. In 1982, the Devesa-Albufera Municipal Service was created, responsible for the development of plans and projects for the conservation and restoration of the wetland.

Sri Songkhram District (Thailand)

The Songkhram River has a basin of 6,473.27 km2 and is an important tributary of the Mekong River. About 54.2% of the overall Songkhram Basin may be classified as “wetlands”, which are significant as a capture fishery providing seasonal employment, income and food to thousands of households. Other products are also sourced from the wetlands by local residents (e.g. mushrooms, bamboo shoots, wild vegetables and reeds). The wetlands, declared as a Ramsar site, are protected as a “community forest” on both sides of the Songkhram River, set up by Thailand’s Royal Forest Department.

ICLEI’s role as partner to the Convention

The Independent Advisory Committee (IAC) governs the Wetland City Accreditation Scheme. This committee reviews the Wetland City Accreditation applications from candidate cities and reports its decision to the Standing Committee of the Convention. ICLEI, along the Convention on Wetlands’ International Organization Partners, promotes the Wetland City Accreditation Scheme and local efforts to gain and maintain its branding. Through ICLEI’s city networks and CitiesWithNature platform, it is well positioned to promote the Wetland City Accreditation brand. During the second triennium from 2019 until 2022, ICLEI has been serving as Co-chair of the IAC, 25 more cities were accredited and they received their award during an Award Ceremony at COP14 in Geneva in 2022.

Urbanization is one of the key defining mega-trends of our time. Four billion people, about half of the world’s population, currently live in urban areas. This number is expected to dramatically increase with the predicted rise in urbanization rates. According to The Nature in the Urban Century report, authored by The Nature Conservancy, Future Earth and The Stockholm Resilience Centre, by 2050, there will be 2.4 billion more people in cities, a rate of urban growth that is equivalent to building a city the population of London every seven weeks. Humanity will urbanize an additional area of 1.2 million km2, larger than the country of Colombia.

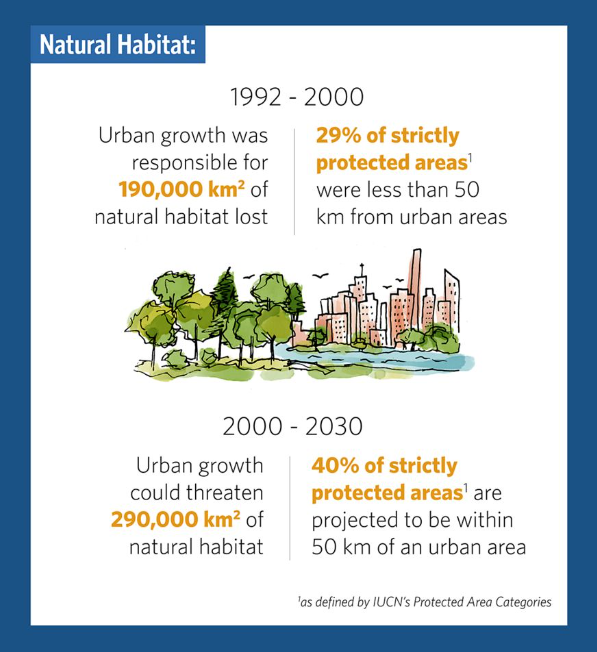

The report also found that if current trends continue over the next two decades, urban growth will threaten more than 290,000 km2 of habitat — an area larger than New Zealand. Protected lands are increasingly in close proximity to cities, with 40% of strictly protected areas anticipated to be within 50 km of a city by 2030.

The urbanization trend poses a major threat to several critical ecosystems, including wetlands. Wetlands can play a crucial role in urban biodiversity, and in maintaining ecosystems and the well-being of urban communities. When preserved and sustainably used, urban wetlands can provide cities with multiple economic, social and cultural benefits. During storms, urban wetlands absorb excess rainfall, which reduces flooding in cities and prevents disasters and their subsequent costs. The abundant vegetation found in urban wetlands acts as a filter for domestic and industrial waste and contribute to improving water quality.

As cities grow and the demand for land use increases, the tendency is for development to encroach on wetlands, because they are often perceived as wastelands that can be used as dumping grounds or converted for other land uses.

Urban wetlands are prized assets, not wasteland, and therefore should be proactively conserved and integrated into the development and management plans of cities. The Convention on Wetlands (also known as the Ramsar Convention) is promoting cities that take exceptional steps to protect their wetlands and benefits to people, by giving credit to cities that prioritize their urban wetlands through an accreditation scheme.

The 172 Contracting Parties to the Convention on Wetlands have agreed to the conservation and wise use of wetlands in their territories. Recognizing the importance of cities and urban wetlands, the Convention introduced a Wetland City accreditation scheme in 2015 (Resolution XII.10). This voluntary scheme provides an opportunity for cities that value their natural and/or human-made wetlands to gain international recognition and positive publicity for their efforts. Cities must apply to be accredited and they have to show that they comply with a number of criteria, including exceptional protection, care and wise use of their wetlands through a range of mechanisms such as urban planning and education.

2018

During the first cycle of the City Accreditation Scheme, the 18 cities that qualified for accreditation were announced at the Convention of Wetlands COP13 in 2018. These 18 cities were:

- China: Changde, Changshu, Dongying, Haerbin, Haikou, Yinchuan

- France: Amiens, Courteranges, Pont Audemer, Saint Omer

- Hungary: Lakes by Tata

- Republic of Korea: Changnyeong, Inje, Jeju, Suncheon

- Madagascar: Mitsinjo

- Sri Lanka: Colombo

- Tunisia: Ghar el Melh

The intention is that The Wetland City Accreditation scheme will encourage cities in close proximity to and dependent on wetlands, especially Wetlands of International Importance, to highlight and strengthen a positive relationship with these valuable ecosystems, for example through increased public awareness of wetlands and participation in municipal planning and decision-making. The Accreditation scheme should further promote the conservation and wise use of urban and peri-urban wetlands, as well as sustainable socio-economic benefits for local people.

During the 59th meeting of the Convention on Wetlands Standing Committee on 26 May 2022, the Co-Chairs of the Convention on Wetlands Independent Advisory Committee on Wetland City Accreditation announced that 25 applicant cities had been accepted in recognition of their exceptional efforts to safeguard urban wetlands for people and nature.

Congratulations to the cities that have been accredited! One of the cities, Cape Town, is one of the pioneer CitiesWithNature – a global partnership initiative that recognizes and enhances the value of nature in and around cities across the world. The 2022 accredited cities are:

2022

During the second cycle of the City Accreditation Scheme, 25 cities qualified for accreditation and were announced during the Convention on Wetlands Standing Committee of May 2022. These newly accredited cities will be formally recognized during the COP14 of the Convention on Wetlands, to be held in November 2022.

These 25 cities are:

- Canada: Sackville

- China: Hefei; Jining; Liangping; Nanchang; Panjin; Wuhan; and Yangcheng

- France: Belval-en-Argonne and Seltz

- Indonesia: Surabaya and Tanjung Jabung Timur

- Islamic Republic of Iran: Bandar Khamir and Varzaneh

- Iraq: Al Chibayish

- Japan: Izumi and Niigata

- Morocco: Ifrane

- Republic of Korea: Gochang; Seocheon; and Seogwipo

- Rwanda: Kigali

- South Africa: Cape Town

- Spain: Valencia

- Thailand: Sri Songkhram District