Malmö: Where indigenous birds mingle with global travellers

About the author:

Erik Hirschfeld is a well-known Swedish birder fortunate to live in Malmö. He is the author of several books, including The World’s Rarest Birds (2013) covering global bird conservation and Fåglarnas Malmö (2011), covering Malmö’s birds and their interaction with humans. He has served on bird record committees in Sweden, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates, and has been involved in several scientific expeditions, especially in the Middle East. Fifteen years ago he founded Vilda Malmö, initially a lose network of nature guides, in order to highlight Malmö’s natural environment to its residents. Today he spends his birding time between being an active bird bander, studying migration of seabirds, and running Scandinavia’s largest bird tour company, AviFauna. He frequently gives illustrated talks on birds to both beginners and professionals, and guides people interested in birds for Vilda Malmö.

A crossroads for migration

Perched at the southern tip of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Malmö offers migratory birds a convenient shortcut across the water to Denmark and mainland Europe. Much like the famed Falsterbo, just 30 km down the coast, Malmö is perfectly positioned along a major migratory route. When on the move, many landbirds avoid vast bodies of water and instead funnel through areas with shorter crossings. Add the iconic Öresund Bridge into the mix, and you’ve got a ready-made flight path. On windy days, birds of prey can often be seen using the bridge as a navigational aid during their spring and autumn journeys.

But geography alone doesn’t explain Malmö’s birding success. Migrants won’t stop unless there’s a good reason to. That’s where Malmö’s clever city planning and habitat diversity come into play. The city is a patchwork of microhabitats catering to a dazzling variety of birds with different needs.

Red-necked Grebes

Black Redstarts (male & female)

Habitat hotspots and urban adaptations

Take the coastline, for instance. Stretching out in a mix of sandy, muddy, and rocky areas, it serves up a smorgasbord of habitats for wading birds, perfect for sanderlings, bar-tailed godwits, and purple sandpipers. In the harbour, boulders placed as wave-breakers become life-saving shelters for tired migrant passerines hiding from hungry sparrowhawks. Seabirds following the east-west coast are often seen rerouting dramatically to avoid land, providing unforgettable spectacles for those positioned at just the right windy vantage point. In fact, gannets now winter offshore in large numbers, mingling with massive flocks of cormorants. Two species of albatross have even made surprise appearances here, an astonishing rarity in these parts, and sooty shearwaters from New Zealand have become almost annual guests.

One of Malmö’s most productive hotspots is the stretch along Ribersborg Beach. Here, seaweed is cleared to please beachgoers and then dumped near a hedge by Lagunen harbour. That unassuming pile teems with insect life and sits beside a dense alley of trees, offering both food and shelter to weary warblers. Come migration season, that compost pile becomes a lifeline. It’s also the site of an ongoing bird banding project, and when the seaweed dries out, it’s used to fertilise Malmö’s public lawns, an example of ecology in action.

Inland, a series of freshwater ponds offers safe nesting and feeding areas to mute swans, little grebes, and the red-necked grebe, a striking species whose springtime courtship dances can be enjoyed up close, even without binoculars. These ponds give Malmö residents front-row seats to one of nature’s most theatrical performances.

Oystercatcher

Barnacle Geese

Red-necked Grebe

Common Gull

Barnacle Geese

Barnacle Geese with two rare Red-breasted Geese

Birds in the parks and cemeteries

Every spring, a headline act unfolds in the city. Ravens nest in an old shipbuilding crane beside a waterfront residential zone, an urban first in Sweden. Unlike the domesticated Tower of London ravens, these are wild birds, voluntarily choosing Malmö’s industrial relics as breeding grounds.

The city’s beloved parks are no less impressive. Hammars Park, with its wild undergrowth, attracts songbirds like blackcaps, wood warblers, and goldfinches. Pildammsparken, with its elegant promenade and wide pond, plays host to ducks, gulls, and breeding great crested grebes showing off their curious greeting displays in spring. It’s a favourite among preschoolers, grandparents, and birders alike, offering easy access and rich wildlife. Slottsparken, meanwhile, offers a blend of trees and water that appeals to both breeders and migrants.

In late morning, gulls descend from the coast to bathe in the parks’ freshwaters. Tufted ducks and common gulls, with nesting grounds as far away as Siberia, make Malmö their winter base. Come late February, they’re joined by the first migrant lesser black-backed gulls, newly arrived from central and eastern Africa. Meanwhile, black-headed gulls spend the colder months here after journeys from Finland and the Baltics. Banded individuals, some as old as 30, have revealed fascinating life histories stretching across multiple cities and countries. The combination of being raised and spending the winter in highly urbanized habitats seems to be favorable to longevity.

St Pauli Cemetery, oriented north to south, is another seasonal hotspot, especially in spring. Here, you might glimpse the cryptic wryneck or the elusive ring ouzel, more commonly found in the remote fjells of summer. Redstarts regularly nest here too, making the cemeteries a true urban oasis.

Rooftop nesters and winter guests

Even Malmö’s high-rises play a part. Districts like Västra Hamnen, Dockan, and Limhamns Sjöstad resemble mountainous terrain to birds like the black redstart, which now echo their melodic calls through Malmö’s urban canyons. Some individuals even winter here, finding refuge in the evergreen ivy on buildings near the central station, alongside European robins.

The charismatic oystercatcher also makes its urban presence felt. Arriving in late February, they roost in flocks on jetties used by swimmers in summer before fanning out to nest on flat rooftops. Common gulls, meanwhile, often share these rooftops, while house martins and common swifts each have their architectural preferences. Clay nests on high buildings suit the martins, while the swifts prefer roof tiles on villas in Malmö’s western suburbs.

And let’s not forget the barnacle geese. Once Arctic-bound migrants, they now breed in Malmö in huge numbers, a mix of introduced birds and natural colonists. In May, local geese look skyward as their distant cousins pass overhead in dramatic, noisy formations, en route between the Low Countries and their Novaya Zemlya breeding grounds. Some Malmö-born geese have even been spotted in the Arctic, and vice versa.

Oystercatchers

Of course, the benefits of this biodiversity aren’t just for the birds. Access to urban nature is known to boost human well-being, and Malmö makes it easy to connect with the wild. Through the Vilda Malmö (Wild Malmö) program, residents can join free expert-led tours covering birds, bats, trees, marine life, and more, kept to small, intimate groups. For those who prefer to look for urban wildlife on their own, there are information signs placed around the city, with photos or drawings of the local fauna.

Malmö’s love of birds runs deep. Even its bird alert app, usually the domain of avid birders, has over 1,000 subscribers, proving that in this city, the skies above are just as captivating as the streets below.

Urbanization is one of the key defining mega-trends of our time. Four billion people, about half of the world’s population, currently live in urban areas. This number is expected to dramatically increase with the predicted rise in urbanization rates. According to The Nature in the Urban Century report, authored by The Nature Conservancy, Future Earth and The Stockholm Resilience Centre, by 2050, there will be 2.4 billion more people in cities, a rate of urban growth that is equivalent to building a city the population of London every seven weeks. Humanity will urbanize an additional area of 1.2 million km2, larger than the country of Colombia.

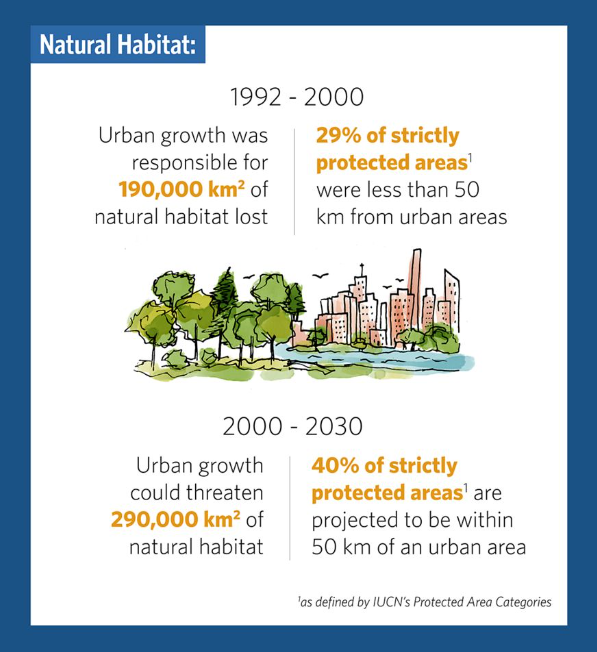

The report also found that if current trends continue over the next two decades, urban growth will threaten more than 290,000 km2 of habitat — an area larger than New Zealand. Protected lands are increasingly in close proximity to cities, with 40% of strictly protected areas anticipated to be within 50 km of a city by 2030.

The urbanization trend poses a major threat to several critical ecosystems, including wetlands. Wetlands can play a crucial role in urban biodiversity, and in maintaining ecosystems and the well-being of urban communities. When preserved and sustainably used, urban wetlands can provide cities with multiple economic, social and cultural benefits. During storms, urban wetlands absorb excess rainfall, which reduces flooding in cities and prevents disasters and their subsequent costs. The abundant vegetation found in urban wetlands acts as a filter for domestic and industrial waste and contribute to improving water quality.

As cities grow and the demand for land use increases, the tendency is for development to encroach on wetlands, because they are often perceived as wastelands that can be used as dumping grounds or converted for other land uses.

Urban wetlands are prized assets, not wasteland, and therefore should be proactively conserved and integrated into the development and management plans of cities. The Convention on Wetlands (also known as the Ramsar Convention) is promoting cities that take exceptional steps to protect their wetlands and benefits to people, by giving credit to cities that prioritize their urban wetlands through an accreditation scheme.

The 172 Contracting Parties to the Convention on Wetlands have agreed to the conservation and wise use of wetlands in their territories. Recognizing the importance of cities and urban wetlands, the Convention introduced a Wetland City accreditation scheme in 2015 (Resolution XII.10). This voluntary scheme provides an opportunity for cities that value their natural and/or human-made wetlands to gain international recognition and positive publicity for their efforts. Cities must apply to be accredited and they have to show that they comply with a number of criteria, including exceptional protection, care and wise use of their wetlands through a range of mechanisms such as urban planning and education.

2018

During the first cycle of the City Accreditation Scheme, the 18 cities that qualified for accreditation were announced at the Convention of Wetlands COP13 in 2018. These 18 cities were:

- China: Changde, Changshu, Dongying, Haerbin, Haikou, Yinchuan

- France: Amiens, Courteranges, Pont Audemer, Saint Omer

- Hungary: Lakes by Tata

- Republic of Korea: Changnyeong, Inje, Jeju, Suncheon

- Madagascar: Mitsinjo

- Sri Lanka: Colombo

- Tunisia: Ghar el Melh

The intention is that The Wetland City Accreditation scheme will encourage cities in close proximity to and dependent on wetlands, especially Wetlands of International Importance, to highlight and strengthen a positive relationship with these valuable ecosystems, for example through increased public awareness of wetlands and participation in municipal planning and decision-making. The Accreditation scheme should further promote the conservation and wise use of urban and peri-urban wetlands, as well as sustainable socio-economic benefits for local people.

During the 59th meeting of the Convention on Wetlands Standing Committee on 26 May 2022, the Co-Chairs of the Convention on Wetlands Independent Advisory Committee on Wetland City Accreditation announced that 25 applicant cities had been accepted in recognition of their exceptional efforts to safeguard urban wetlands for people and nature.

Congratulations to the cities that have been accredited! One of the cities, Cape Town, is one of the pioneer CitiesWithNature – a global partnership initiative that recognizes and enhances the value of nature in and around cities across the world. The 2022 accredited cities are:

2022

During the second cycle of the City Accreditation Scheme, 25 cities qualified for accreditation and were announced during the Convention on Wetlands Standing Committee of May 2022. These newly accredited cities will be formally recognized during the COP14 of the Convention on Wetlands, to be held in November 2022.

These 25 cities are:

- Canada: Sackville

- China: Hefei; Jining; Liangping; Nanchang; Panjin; Wuhan; and Yangcheng

- France: Belval-en-Argonne and Seltz

- Indonesia: Surabaya and Tanjung Jabung Timur

- Islamic Republic of Iran: Bandar Khamir and Varzaneh

- Iraq: Al Chibayish

- Japan: Izumi and Niigata

- Morocco: Ifrane

- Republic of Korea: Gochang; Seocheon; and Seogwipo

- Rwanda: Kigali

- South Africa: Cape Town

- Spain: Valencia

- Thailand: Sri Songkhram District